Crack Lm Hash Nt Hash Decrypt

In part 1 we looked how to dump the password hashes from a Domain Controller using NtdsAudit. Now we need to crack the hashes to get the clear-text passwords.

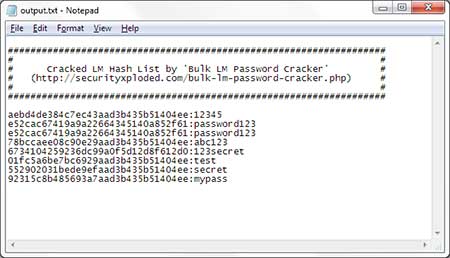

LM and NTLM Hash decryption - waraxe forums topic. Hey there, was wondering if somebody could crack the following LM and NTLM password. Dec 08, 2016 Understanding Password Hashes. There are two password hashes: LM Hashes and NT hashes. LM hashes are very old and so weak even Microsoft has finally stopped using them by default in all Windows versions after Windows XP. NT hashes are Microsoft's 'more secure' hash, used by Windows NT in 1993 and never updated in any way. Welcome to the Offensive Security Rainbow Cracker Enter your Hash and click submit below. Support types: - LAN Manager (LM) - Example.

Hash Types

First a quick introduction about how Windows stores passwords in the NTDS.dit (or local SAM) files. If you’re not interested in the background, feel free to skip this section. Windows stores passwords using two different hashing algorithms – LM (Lan Manager) and NTLM (NT Lan Manager).

LM Hashes

Crack Lm Hashes

The LM hashing algorithm is very old, and is considered very insecure for a number of reasons. Firstly, it is case insensitive, with all letters being converted to uppercase, which greatly reduces the possible keyspace. Secondly, and more importantly, the algorithm pads the password to 14 characters, and then splits it into two 7 character strings, which are hashed separately (using DES). This means that cracking a 14 character password is twice as hard as cracking a 7 character password, rather than being billions of times harder as it would be with an algorithm that did not split the passwords. These, and the fact that the LM algorithm is relatively fast and does not use salts, means that almost any LM hash can be cracked using brute-force or rainbow table attacks in a matter of hours (often minutes or seconds), on commodity hardware. Windows stored both LM and NTLM hashes by default until Windows Vista/Server 2008, from which point only NTLM hashes were stored (along with the empty LM hash AAD3B435B51404EEAAD3B435B51404EE). This means that in a modern environment there should only be LM hashes stored on local systems, but Active Directory makes this a bit more complicated. If the Active Directory domain was created before this change was implemented (on Server 2003 or before), it will still store LM hashes, unless a specific Group Policy setting is configured to prevent the storage of LM hashes. However, configuring this policy does not remove existing LM hashes. Any LM hashes already present will remain until the password for that account is changed. This means that in many domains, there are a small number of accounts that still have LM hashes, which are usually accounts that haven’t had password changes in a number of years (and are quite often privileged or service accounts).

NTLM Hashes

In Windows NT Microsoft introduced the newer NTLM hashes type, which is essentially the MD4 algorithm (so would not be considered secure by modern standards). NTLM fixed the main two problems with LM hashes (case sensitivity and splitting passwords), so in a major improvement in those respects. However, it lacks many of the features of modern hashing algorithms such as Bcrypt or PBKDF2, such as being slow, salting and GPU/FPGA/ASIC resistant.

Tools

There are lots of different tools you can use to crack the password hashes – to some extent it comes down to personal preference. Three of the main ones that people use for AD passwords are Cain and John the Ripper (my personal preference), and Hashcat.

Cain & Abel

Lm Hash Decoder

Cain & Abel is a Windows-based tool with a host of useful features, including a password cracker. Lots of antivirus products incorrectly flag it as malware (mostly due to the Abel component, which can be remotely installed to sniff packets and dump passwords), so your AV may not be happy with you downloading or installing it.

Usage

Cracking passwords with Cain is fairly straightforward. Under the “Cracker” tab, choose “LM & NTLM Hashes” in the bar on the left. You can then right click -> add to list, and import the hashes your pwdump.txt file. Once the hashes are imported, you can select all, right click, and choose one of the cracking options. For each mode you can choose whether to try and crack the LM hashes or NTLM hashes. Cain has three main modes:

Brute Force

Does exactly what it says. It’s single threaded and CPU only, so brute-forcing anything more than 5 characters is unlikely to complete in a reasonable amount of time. However it can be very useful for getting the second half of LM hashes (for example, PASSWORD123 would be stored as two hashes, “PASSWOR” and “D123”). Dictionary Attack Uses a provided wordlist and optionally some permutations. The default Cain wordlist is about 3MB and isn’t bad, but you can get much bigger and better ones online. The “rockyou” wordlist (from the leaked password database of the rockyou website) is a popular choice. The permutations provide a number of options, such as appending numbers of changing the case of the password, however they’re fairly limited and can’t be combined. This is the biggest problem with Cain for password cracking – there’s no rule to capitalise the first letter and append a number, which is what most people do. Because of this, you’ll have much better success with Cain if your wordlist has the first letter capitalised on all the words that if it’s entirely lowercase (which Cain’s default one is). Cryptanalysis Attack (Rainbow Tables) Very effective against LM hashes with either the previously mentioned Ophcrack table, or other larger tables you can get. It’s normally a good idea to break very weak passwords with a simple dictionary attack and short (5 character) bruteforce attack first, then let the Rainbow Tables pick up the rest.

Strengths

The biggest benefit of Cain is that it supports the use of Rainbow Tables for cracking hashes. I won’t go into Rainbow Tables in detail here, but essentially they allow precomputation of password hashes to greatly speed up the cracking process. In practical terms, you can download some (fairly large) tables, and use them to quickly crack hashes. Installing 3d custom girl mods wiki free. They don’t work very well for longer passwords (unless you have terabytes of fast storage), but for shorter passwords they’re extremely effective. Since LM hashes are a maximum of 7 characters long (due to the way the passwords are split), they’re the perfect target for Rainbow Tables. The “XP free fast” tables from Ophcrack are about 700MB, and will crack most LM hashes in a matter of seconds.

Weaknesses

The bruteforce and dictionary modes that Cain provides are fairly limited, and it doesn’t really provide any customisation. The project is also pretty much abandoned, so it’s unlikely there will any new features added in the future. It also only runs on Windows, and is single threaded, so it’s a lot slower than the alternatives. Finally, it doesn’t scale too well to large pwdump files – thousands of users (especially with history) will make it quite unresponsive. It’s good for cracking the LM hashes with Rainbow Tables, or as a basic GUI tool, but beyond that you’re better off using a tools that’s specifically designed for password cracking.

John the Ripper

John the Ripper was originally designed to crack Unix passwords, but now runs on pretty much everything and cracks pretty much any kind of password. The original version is maintained by Openwall who provide the source code and prebuilt Windows binaries. However, there’s a fork (known as the Jumbo version) on GitHub which provides better performance, more hash types, and new attack modes. This is the version that ships in Kali, and I’d highly recommend using it over the original version. There’s also a GUI for it called Johnny, but I’ve never really used this, so can’t comment on it. John stores cracked passwords in a pot file (the default is “john.pot”), and it’s main configuration file is “john.conf” (which will probably be in /etc/john/ on Linux). There are a lot of command line options and further options in the configuration file.

Usage

At the simplest level, you can just point john at a pwdump file, tell it what type of hashes you want it to crack (NTLM) and let it go:

This will perform a number of different attacks (single mode, wordlist mode and incremental mode), but it’s not really the best way to use john. Once it’s finished (although this mode will never finish, so you’ll have to kill it with ctrl+c), you can display the cracked passwords with the show option:

Single Mode Single mode uses information from the pwdump file to try and crack passwords (such as the usernames), as well as some common default passwords and patterns. It’ll probably only take a few minutes (at most) to run and will pick up a decent number of very weak passwords, so it’s usually a good starting point:

Wordlist Mode At the basic level, this is a dictionary attack with a provided wordlist:

Rules However where John starts to shine is the use of password cracking rules. This are similar to the permutations in Cain, but all you a lot more flexibility. A small dictionary with a good set of rules will crack a huge number of passwords, so it really comes down to the quality of the rules you have. Unfortunately the default rules that ship with John are over 15 years old, so aren’t very effective in the days of password complexity. You can try out the default rules with a wordlist:

It should crack a lot more passwords that just the wordlist with no rules, but adding our own rules will make things much better. You can define custom rules in the “john.conf” file. The default rules are defined in the following section:

You can overwrite this section, add your rules here, or create your own rules section. The following rules do some very basic changes (capitalising words, adding 123 or the year, etc). They’re fairly simple and quick to run, but will crack a lot of very weak passwords.

Once these are saved in the configuration file, we can use them by specifying the new “simple” rule set:

The syntax for rules isn’t too complex when you get your head around it, and you can read up the details here if you want to make your own rules. KoreLogic also have a popular set of rules published (although there’s lots of them, so they’ll take a very long time to run). Incremental (bruteforce) Incremental mode is john’s version of a bruteforce attack. Like a normal bruteforce it’ll probably never finish, but it works more intelligently than Cain’s mode. Rather than a simple a-z, it uses an intelligent order based on the most common patterns that occur in passwords. The default charset (where it stores that information) is old, so doesn’t work well, but you can create your own. Once you’ve cracked some passwords, you can create a charset based on those with the following command:

You can then define this charset in John’s configuration file:

And then perform the attack:

Loopback Mode Loopback mode uses all of the previous cracked passwords (from John’s pot) and tries to crack other passwords based on those by permutations (for example changing the number on the end, adding symbols, etc). It’s very effective once you’ve cracked a number of passwords and want to find people who are changing their passwords using weak methods (such as incrementing the number of the end each time they change it).

Other Modes There are lots of other modes in john, some of which are really good at cracking more complex passwords (PRINCE), or passwords based on previously seen patterns (markov and mask). You can also apply rules to these other modes and do other interesting things that there isn’t really time to go into here, but there’s plenty of information online about them.

Strengths

John gives you a great deal of customisation, and supports a lot of different cracking modes and hash types. You can also chain together different modes (such as a combined wordlist and mask attack, or applying rules to a PRINCE attack). It can comfortably handle large (multi GB) wordlists and pwdump files (hundreds of thousands of users). Because John has been around for so long there are lots of other tools that are designed to work with it (and its output).

Weaknesses

Although there’s some basic GPU support in the OpenCL builds, it’s not as good as Hashcat’s support (which was very much built with GPU in mind, rather than it being added on decades later). The commandline options can also be a bit finicky, and John can be fussy about the format of some hashes (not usually an issue with pwdump files, but it can be hard to get it to recognise other types).

Hashcat

Hashcat provides much of the same functionality as John (since they’re both open source they merge features from each other), but is built around using the GPU rather than the CPU for cracking. If you have a GPU it will be orders of magnitude faster for most hash types than just using the CPU, so if you’re looking to do password cracking on a system that has GPU(s) then I’d recommend looking into Hashcat. I’ve not used it a huge amount, and some of the syntax is awkward (especially the hash types), so I’m not going to go into detailed usage here, but there are plenty of guides you can find online. If you’re trying to crack as many complex passwords as possible, Hashcat with a decent GPU rig will probably be the best way to go, but if you just want weak passwords, GPUs are probably overkill.

Password Analysis

Part 3 of this series explores some of the different tools and techniques that can be used to obtain useful metrics from cracked password hashes in order to determine improvements to a password policy.

Conclusion

There are lots of different tools and methods you can use for cracking passwords, including plenty that haven’t been touched on at all in this article. Although it’s interesting (and fun) to try and crack as many passwords as you can, really the objective in most cases (certainly for internal auditing) is to identify the weakest passwords, so unless you have other objectives, it’s not worth investing too much time in all the more sophisticated cracking techniques – especially when there are dozens of accounts out there with Password1. In the next post we’ll look at analysing the results of the password cracking and see what useful information and patterns we can identify there.

Background – The SAM

The Windows registry contains a lot of valuable information for cyber investigators and security analysts alike. The registry lives mainly in C:System32config for the local machine, with user specific registry items contained in each user’s profile in a hidden file named NTUSER.DAT. The SAM file is part of the local machine hive and it is where you’ll be able to find information regarding user accounts. This is also where account credentials are stored.

What is an NTLM hash?

New Technology LAN Manager, or NTLM is a protocol suite in Windows that maintains authentication. The NTLM hash is unsalted, meaning that it is not modified with a known value. This enables the NTLM hash to be used in a practice called “Pass the Hash” where the hash value is used for authentication directly. The NTLM hash appears in the following format:

Fallout 1 emulator mac download. The information can be broken down into three sections. The first shows a username followed by a colon and double quotes. The colon and quotes can be safely ignored as they are not needed to crack the password. A user’s relative identifier would appear in this spot (500 for Administrator, 501 for Guest, 1000 for first user created account). The next string of characters is the LM hash and is only include for backwards compatibility. The last section is the most important for cracking, this is the NT hash. The NT hash is commonly referred to as the NTLM hash, which can be confusing at the start.

How do you get the NTLM hash?

The answer to this depends on the target system state. Mimikatz is likely the most popular tool for the job. If it is powered down, then the targets hard drive can be removed and mounted (ideally with a write blocker) and the registry files can be accessed. In this scenario, Mimikatz will be used against the SAM file and the SYSTEM file. An example of the command can be seen below.

Defeating the Hash

Once the NTLM hash has been obtained, there are several methods of determining the plain text password. Bear in mind that cryptographic hashes are one-way-functions that cannot be decoded. In order to determine the actual password, we must compare the hashes of known strings to determine if it is a match to the sample.

Cracking

Depending on the hardware of a computer, this method could take anywhere from hours to weeks. I will cover the process I took to begin cracking the hashes. There are various tools available, but I will be focusing a tool named Hashcat due to familiarity. Hashcat, is an opensource password hashing suite that can leverage the power of graphics cards to aid in the calculations. Hashcat itself supports cracking via a dictionary, bruteforce, or a combination there-of. A straight dictionary attack would be the fastest method, but it would require that the password be in the dictionary verbatim. A collection of wordlists can be found on GitHub with the correct search term. A bruteforce method would be slow, but as long as the mask matches it is a more inclusive search method.

In the above screenshot, I chose to use a GUI frontend on Hashcat for demonstration purposes. I’ll be starting a bruteforce attack assuming the password is between 1 and 9 characters in length and has uppercase, lowercase, and/or numbers in it. This can be seen by the character set #1 with ?l?d?u. The question mark here is used as a wildcard.

Hashcat will then try all the possible solutions to match the sample hash. In my case it is working at 7466MH/s (or 7,466,000,000 hashes a second). Even with the speed, this will take time.

There must be a better way

I am a firm believer that success in this field has a big part to do with being able to recognize when someone has already done the hard work for you. Most of the time you can find the answers you are looking for by asking the right question to the all-knowing Google. A quick search for NTLM hash cracker will return with a website called hashkiller.co.uk, which just happens to be who created the GUI for Hashcat.

Here, we can take the NT hash from the provided list and see if they have been seen before. I’ll be using the following as an example. The NT hash is highlighted.

Perfect, the password to the user account “cmonster” is “cookie”. This method works for most of the hashes found on the list. There are a few that are not found. I have listed them below.

You may have noticed that the hash for “Guest” and “victim” are identical, they must have the same password. We find one, we find both. My thought process for this part of the challenge was to return to Google and ask a different question. Knowing that a hash is a unique string, I figured it might be worth while to paste the hash directly into the search box and see what it returns. Perhaps it’s referenced elsewhere.

I stumbled upon the answer in the very first result. It became very obvious to me.

The account I was attempting to find the password for was Guest. The Guest account (sid 501) in Windows does not have a password by default, so it would make sense that it is blank. This must also be true for the victim account.

Unfortunately, I was unable to find any matches to two of the hashes using the easy method. My computer will be set to manual crack these two hashes over the next 8 weeks.

Below are the hashes that were able to be defeated using simple research and online tools.